By Farooq A. Kperogi, Ph.D. Twitter: @farooqkperogi Doublespeak is intentional manipulation of language to conceal uncomfortable ...

By Farooq A. Kperogi, Ph.D.

Twitter: @farooqkperogi

Doublespeak is intentional manipulation of language to conceal

uncomfortable truths or to cleverly tell outright lies. The term came to us

from George Orwell, although he didn’t use it himself. The term he used in his

famous book titled 1984 is “newspeak,”

which he said consists in limiting the range of words people use and in

stripping language of semantic precision in order to facilitate government

propaganda and mind management.

The mainstreaming of Orwellian

doublespeak in Trump’s America is already causing an enormous spike in the

sales of Orwell’s 1984, which was

first published in 1949, especially after a Trump administration official by

the name of Kellyanne Conway defended habitually intentional falsehoods by the

Trump administration as merely “alternative facts.”

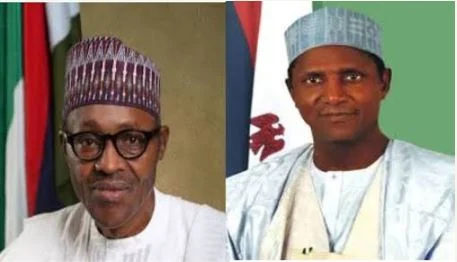

All governments lie, but the brazenness and consistency of the

lies of the Buhari government are simply remarkable. It competes favorably with

the Trump administration in prevarications and loud, bold defiance of basic ethical proprieties. Nowhere has this become more apparent in recent time than

in the information that government officials share with the Nigerian public

about President Muhammadu Buhari’s health.

I have no evidence for this,

but my hunch tells me that Buhari isn’t nearly as sick as his detractors make

it seem, but the illogic, intentionally deceitful and mutually contradictory

language of government spokespeople in explaining away the president’s

prolonged absence from Nigeria have conspired to fuel unhealthy speculations about

the state of his health.

As I told the BBC World Service in a February 7, 2017 interview,

the labyrinth of tortuous lies, fibs, half-truths, and conscious deceit that

emanate from the government make it impossible to even guess the truth.

The president’s media advisers admit that the president is in

London on a “medical vacation” (which is doublespeak for “he is sick and needs

medical attention”), and his latest letter to the National Assembly said he was

awaiting the results of medical tests, but the Acting President and the

Minister of Information say he is “hale and hearty” (which means he is vigorous

and doing well). No one can be simultaneously on a “medical vacation,” be

awaiting the results of medical tests, and be “hale and hearty.” That’s a

logical impossibility.

It gets even stranger. Senator Abu Ibrahim, a senator from Katsina

State who said he was in touch with the president, told newsmen that the

president was neither on medical vacation nor hale and hearty, but only “exhausted

by the weight of the problems the country is going through.” So London is the

president’s destination of choice to rest, while millions of people who voted

him into office squirm in the severe existential torment his administration

either deepened or caused? Interesting!

On February 7, Presidential Media Adviser Femi Adesina also told

Channels TV that he was "daily" in touch with the President, but

doesn't "speak with him direct." How does one "keep in

touch" with someone thousands of miles away without "directly

speaking" with him?

Well, Adesina said he does that by being "in touch with London

daily." I am not making this up. You can watch the interview on ChannelTV’s

YouTube channel. But it gets worse still. He added: "People around him

will speak daily. Daily." You would think the word "daily" was

in danger of going out of circulation and needed to be verbally curated on

national TV.

This doublespeak recalls my

grammar column of December 10, 2009 on the late President Yar'adua's health. It

was titled “Yar’adua’s Health: Amb. Aminchi’s Impossible Grammatical Logic.” Read

it below and note the similarities with what is going on now. Enjoy:

Nigeria’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Alhaji Garba Aminchi, was

quoted by an Abuja newspaper to have fulminated against the

unnervingly prevailing buzz that President Yar’adua is in a persistent

vegetative state and in grave danger of imminent death. “And all these

insinuations are lies,” he was quoted to have said. “To the best of my

knowledge, I see him every day, and he is recovering….”

To the best of his

knowledge, he sees the ailing president every day? So our ambassador is not

even sure if, indeed, he sees the president every day, but he is certain

nonetheless that the president is recovering. Huh? This is a supreme

instantiation of a case where thought, language, and materiality have parted

company.

At issue here is

the idiom “to the best of my knowledge,” which is also commonly rendered as “to

my knowledge.” This expression, according to the Macmillan Dictionary, is used for

saying that you think something is true, but you are not completely certain, as

in, “To the best of my knowledge, the President has not decided if he will

resign because of his failing health.” The Free Dictionary defines the idiom thus: “as I

understand it.” The Oxford Dictionary also defines it as, “from the information

you have, although you may not know everything.”

So, the idiom is

deployed principally to express thought-processes that reside in the province

of incertitude, of inexactitude. If, for instance, someone were to ask me (and

somebody did indeed ask me a couple of days ago) if Yar’adua was dead, I would

say “well, to the best of my knowledge he is alive.” Here, the phrase “to the

best of my knowledge” admits of both the possibility that he could be alive or

dead. In other words, it betrays the uncertainty and tentativeness of the

information I have about the query.

Now, for Ambassador

Aminchi to use the idiom “to the best of my knowledge” (which admits of

uncertainty) in the same sentence as “I see him every day and he is recovering”

(which connotes cocksure certitude) evokes an eerily bizarre disjunction

between thought, speech, and reality, one that is impossible to conceive of

even with the wildest stretch of fantasy. This is as much a grammatical slip as

it is a logical labyrinth.

One perfectly

legitimate interpretive possibility from the ambassador’s statement is that he

actually sees a figure in Saudi Arabia in the likeness of President Yar’adua

that is convalescing from a sickness, but is uncertain if this is merely the

apparition of a spooky specter masquerading as Yar’adua or if it’s Yar’adua

himself. In spite of this dubiety, however, he is positive that the real

Yar’adua is recuperating.

This is obviously

not what the ambassador wants to be understood as saying. So, one or two of

three things are happening here. The first is that the ambassador is being

barefacedly mendacious in order to conceal the graveness of the condition of

Yar’adua’s health. And this won’t be out of character. After all, English

diplomat and writer Henry Wotton once famously defined an ambassador as an

"honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country." Only

that, in this case, our ambassador is lying abroad for the bad of his country.

The second

possibility is that the ambassador is simply clueless about the meaning of the

idiom. And a third possibility is that he has been misquoted or mistranslated

by the reporter who wrote the story.

Now, this isn’t an

idle, nitpicking censure of an ambassador’s innocent slip by a snooty,

self-appointed grammar police. This issue is not only about the health of

Yar’adua; it is also about the health of our country. Since Yar’adua took

critically ill, the nation has been in even much graver illness. In somber

moments such as this, we cannot afford the luxury of tolerating intentionally

deceitful and irresponsible political language from public officials.

Link between Bad Language

and Misgovernance

In his famous 1946

essay titled “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell railed against this very

tendency among the public officials of his day. He wrote: “Political speech and

writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things like the

continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the

dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by

arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square

with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has

to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.”

Do you see any

parallels here between Ambassador Aminchi’s illogical grammar—and indeed that

of most Nigerian public officials—and the public officials of Orwell’s days?

Interestingly, the

problem endures to this day even in Britain. On Nov. 3, 2009 the Guardian of London reported that a British parliamentary committee

excoriated “politicians and civil servants for their poor command of the

English language” epitomized in the “misleading and vague official language” of

prominent politicians.

Tony Wright,

chairman of the committee, said: “Good government requires good language, while

bad language is a sign of poor government. We propose that cases of bad

official language should be treated as ‘maladministration’.”

Maybe the

committee chairman’s sentiments are a bit of a rhetorical stretch, but someone

should tell Ambassador Aminchi that he cannot simultaneously be unsure that he

sees the ailing president and yet be certain that the president is recovering.

That’s impossible grammatical logic. And that can only sprout from a mind that

is wracked by psychic disarray.

No comments

Share your thoughts and opinions here. I read and appreciate all comments posted here. But I implore you to be respectful and professional. Trolls will be removed and toxic comments will be deleted.